I am fortunate to travel a fair amount and count numerous international artists among my friends. Over a decade ago, I was invited to read my poetry in Bratislava, Slovakia:

There, I had the good luck to meet poets that I am still in touch with who, in turn, introduced me to artists/thinkers from their own culture that I would never have been aware of otherwise.

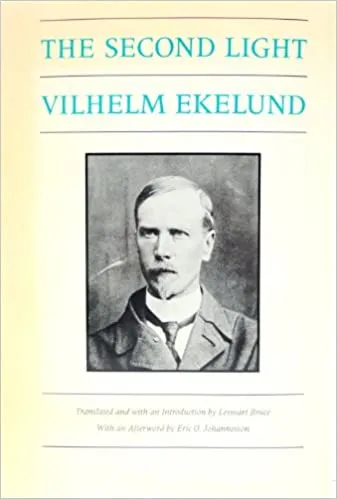

Swedish poet, Boel Schenlaer, whom I met in Slovakia and am still friends with, introduced me to a great Swedish poet, Vilhelm Ekelund (1880-1949) who was something of a revelation for me.

I regard Ekelund as a kind of literary soul-gazer: somewhere between a philosopher and a mystic. Here's an example of his inspired prose:

There are passages in the works of some authors that in a way lie outside the frame of their writing. Passages where you suddenly feel the man talking is not the literary worker So-and-So, but the human being high above all ‘literature.’ Clear, deep, good—but also with a wild tone, flying through the soul, like the scream of a bird above a desolate ocean bay.”

Another great writer, Austrian poet and novelist, Rilke, writes:

“Space reaches from us and construes the world. / To know a tree in its true element, / throw inner-space around it, from that pure / abundance in you.”

I think there are certain types of unclassifiable writers who cultivate these exquisite states, in order to intensify their inwardness and access the numinous.

Back to Ekelund, who writes:

How did I become a hunter for treasure? When I saw a climate (a land) in my nature, in the traditions of my blood which was my heritage. Then I began to realize that the strife of my whole existence was this: to prove my right to inherit . . .

Thank you, Boel, and the international literary festival in Slovakia, for fatefully introducing me this marvelous figure. At the time, I remember that I was raving about Nietzsche and the aphorism, presumptively, as it turned out.

“You must read Ekelund,” Boel insisted.

I knew immediately upon opening the first book. The way you know when you meet people. Ekelund was born in 1880 (Nietzsche was still around then) and died in 1949. He began as a poet, and a gifted, accomplished poet, so that by twenty-three years of age he was considered Sweden’s foremost poet.

Then, being the radical temperament that he must have been, he renounced poetry as sentimental and did not publish any more verse. Instead, he practiced a kind of literary soul-gazing.

“Books must be lived to be read,” he writes. He saw into the writers he read in ways that others don’t. He composed essays and aphorisms. For example, he discovered Nietzsche at twenty-seven. He turned to Nietzsche “for learning, strength and solace.”

Nietzsche taught him that it is possible to be a great poet of ideas writing in prose. By his forties, Ekelund wrote exclusively in aphorisms. The aphorism integrates both existential and moral commitment, and that is what Ekelund was after. No less!

Ekelund writes:

An even accumulation of divine sunshine, slow and blissful, no artist’s fever with repercussions of tumbling into darkness. My worship of the sun begins in the autumn, culminates in February.

Ekelund writes:

The real poet is a mystic.

Ekelund would not write for money and lived sometimes in the most heartbreaking poverty. He tied a rope around his waist for a belt and slept as a vagrant. He led a terrible life and desperate.

(He didn’t have Rilke’s gift for cultivating princesses and baronesses.)

He collapsed with a lung ailment and was in recovery when he wrote The Second Light.

As he was recovering, he began to hear himself breathe, and with that awareness his breath changed altogether. He was quieted somehow. Nietzsche had advised that no thoughts could be trusted but those that came to one while walking. Ekelund, who would never stop thinking, took this advice for his medicine.